Most of us have a general idea of the functions of sperm cells. You may think of them looking like miniature tadpoles, busily swimming their way towards an egg. The result would be a human embryo which, all being well, will implant inside the female uterus and continue in its development until the moment a baby is born. But how much do we really know about these highly specialised cells, the sex cells known as gametes? How much do we understand the function of sperm cells and egg cells, those basic building blocks of every new life that ever came into the world?

This article delves into the microscopic world of those powerhouses of potential, the human gametes. We take a look through the microscope to illuminate how sperm and egg cells are adapted to their function of human reproduction and how, when the two come together, whether naturally or in the laboratory, they fuse to become a new single cell with the potential for a new life.

How is sperm adapted to its function?

Unlike women, who are born with all the eggs they will ever have, men are not born with a limited supply of sperm per se. The sperm cells are made in the testes, beginning at puberty when testosterone levels start to rise, and this continues throughout life, even though numbers and quality decline with age. The process of sperm production, triggered by testosterone and involving the luteinising hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), is known as spermatogenesis. Spermatogenesis takes around 74 days to complete.

What do sperm cells look like?

The structure of sperm cells reflects its one purpose: to fertilise an egg, pass on its genetic information and produce the next generation.

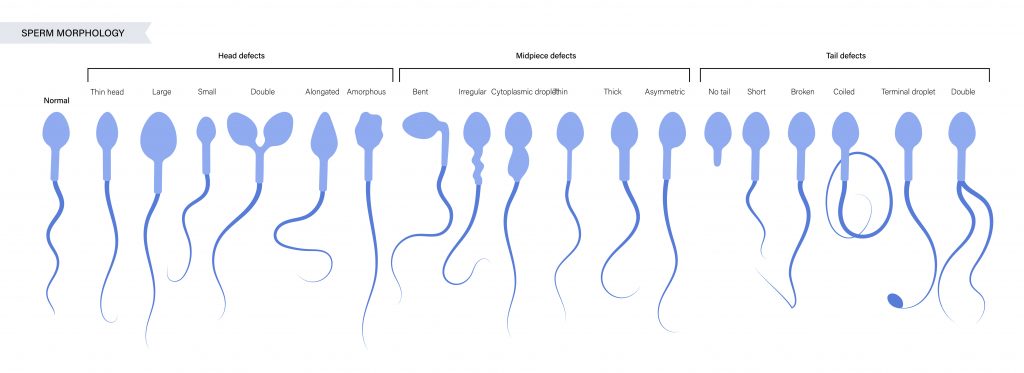

- Sperm structure, or sperm morphology, includes a head, body and tail. However, all sperm do not necessarily look alike; any part can have a different shape and size or differ in their ability to move and swim (known as their motility).

- The sperm head is smooth and oval, resembling an egg, with a length-to-width ratio of 1.50:1.70. The head contains the nucleus that carries the genetic material of 23 chromosomes. The acrosomal cap surrounds the sperm head and is important in recognising the egg. It contains molecules which, when they come into contact with diffusible molecules from the egg, enzymes stimulate the sperm to swim in the right direction – that is, towards the egg. The acrosome also contains inactive enzymes. When coming into contact with the proteins of the egg’s membrane, the enzymes are converted into an active form capable of acting on the membrane, allowing the sperm to penetrate and enter the egg.

- The middle section, or midpiece of the sperm, is the central part between the head and tail. Like the head, it takes up around 10% of the overall length, but unlike the head, it does not contain genetic material. In fact, the midpiece contains tightly concentrated mitochondria, the source of energy that allows the sperm to swim to its target.

- The tail section of the sperm is an elongated, thin structure, making up about 80% of the total length. Known as the flagellum, it provides the wave structure that allows for forward movement and has a circular propeller-like waveform motion.

These features add up to a structure that makes sperm cells superbly adapted to their function. The streamlined design allows rapid movement in search of its target, while the tapered head reduces drag as it travels. The tightly packed mitochondria in the middle section provide the energy required for movement and are discarded after the sperm head has successfully penetrated the egg. The acrosome is crucial in identifying the target and contains enzymes needed to soften the egg’s outer membrane, allowing penetration.

How is an egg cell adapted to its function?

The female egg cell is the largest single cell in the human body – nearly 10,000 times bigger than a sperm cell. But, just like sperm, it has adaptations to its structure, formation and genetic composition that allow it to function in line with its purpose. The genetic makeup of eggs is similar to sperm, but their structure is entirely different.

While sperm cells are adapted for mobility, egg cells are adapted to support a new organism.

They need to be much larger than sperm, not because they contain more chromosomal material (which, in fact, equals that of sperm), but because they need a much greater volume of cytoplasm. This semi-fluid substance provides nutrients for the developing embryo before implantation takes place.

Egg cells are formed differently from sperm.

In the case of sperm, one parent cell produces four sperm cells. For eggs, however, one parent cell produces a single egg cell plus three ‘polar bodies’, which are biologically necessary to maintain the correct number of chromosomes. These quickly degrade to be reabsorbed by the body, leaving one comparatively large egg cell with the right number of chromosomes and all the cytoplasm it will need if it is fertilised.

What happens if the egg or the sperm don’t function as expected?

Those of us working in the field of reproductive medicine have found that it’s possible to work directly with sperm cells to increase the chances of conception. Egg cells are more challenging to work with because they are so delicate, but when problems arise, there are still plenty of potential solutions. Here are some examples:

When sperm or eggs need a helping hand

- Poor sperm quality: One of the most common causes of male infertility is poor-quality sperm. A poor-quality semen sample contains a large number of sperm that do not have an ideal shape (morphology) or do not swim very well (motility). In both cases, we have assisted fertility techniques, such as Intracytoplasmic Sperm Injection (ICSI) that can help. With this technique, we select only the healthiest sperm from a sample and microinject a single sperm cell straight into an egg. It can be performed as part of an In Vitro Fertilisation (IVF) treatment.

- Low sperm count: Although this may not be a problem with sperm cell function per se, having a low sperm count – where there is a low concentration or absence of sperm in the semen – is one of the most common causes of male infertility.

- Lack of eggs: Likewise, one of the most frequent problems we encounter with the availability of eggs is either due to irregular ovulation, caused by conditions such as PCOS, or blockages within the fallopian tubes, such as fibroids or conditions like endometriosis. In the latter, this means that although ovulation is taking place, the eggs may be obstructed from reaching the womb. One solution to both of these issues is IVF. As part of the IVF process, multiple eggs are grown in the ovaries, helped by gentle hormonal stimulation. We collect the eggs in a short surgical procedure when they are mature. Fertilisation takes place in the laboratory, bypassing the fallopian tube altogether.

When egg or sperm cells are not quite operating smoothly in any particular respect, all is not lost. If you have concerns about your fertility or would like to speak to one of our experienced specialists, feel free to contact us at IVI.

Comments are closed here.